Sample Aphorisms 1943 to 1944 (of hundreds)

Character

A man who eats well, drinks well and loves well is not necessarily a pig; a man who does not eat well, drink and love well is not necessarily a gentleman either.

Honesty is the dilemma between the Cash and the Cashier.

More people have gone mad by putting on crazy airs than by mental exhaustion.

If people would watch ants and bees with the same keen interest as they watch all-in-wrestling, all of us would be sports.

Sociology

Rubbing shoulders with high class does not remove the dust from your shoes.

Class-consciousness in degrees; People bath in water; goddesses in milk; man gods in blood.

The major trouble of aristocracy is that it is only a minority.

If good and bad should be judged by racial colour-schemes, ranging from black to white, Plato would have to step out of his grave, remove his eternal

ethics and ideals from the museums to the cosmetics and have them paroxided and permanent-waved.

War - Peace

War is the menstruation of Mother Earth.

War is man's misinterpretation of nature's will to control the proportion between life and death within reason; man does it without reason.

1939 was the Doomsday of Heaven. The devil tore up the agreement between good and evil.

As a sword and the cross are inseparably alike, so are war and peace.

Education

If you want to learn how to jump high and fall again on your feet, do not ask your teacher, ask your cat.

Libraries and Zoos are the two most important municipal buildings; libraries to make us forget where we came from, and zoos to remind us.

Introduction to Carved Thoughts (1945)

The Conscription

Board of Nature’s Army fixed my birth date for the year 1908 at Kolozsvar, one

of the most cultured cities of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. The majestic

and beautifully sculptured mountains that surround my native city inspired my

imagination with the desire to become a sculptor. Though the religious environment into which I was born seemed

to clash with my calling, later when I discovered that religion and art do not

ultimately exclude each other, but go hand in hand, my mind was at peace and I

accepted the calling.

My first attempt at

sculpturing started with carving pieces of rubber that I stole from my

school-mates in the primary school – a material which my school friends

used for wiping out things instead of creating it into something that remains

for ever. This fundamental difference between my friends and myself has

remained in the idea that artists will create everlasting values out of matter

which is of no value to the general public.

Having failed in most

of the subjects I was taught at school, except carving, reciting and singing,

there was nothing left for me but to follow the call of the mountains. I ran

away from home to a place in which besides a market for cattle, vegetables and

fruit, there was also a market for Bible teachers. My higher appetite, however, was not

satisfied. This dissatisfaction

was aggravated by the police who were sent after me and who, instead of terrorizing

run-aways trying to follow their true ambition, should help them to attain that

vocation.

On my voluntary

return home, conflicts between religious, material and social values were the

same as before, and temptations were abundant. Wine, women and song, the food

of the Gods, were stretching out their hands all around me. The religious

mission of carrying home the red wine which a pious bottle-storekeeper used to

offer periodically to the priestly office of my Father, was one of my best

adventures, for I never missed the opportunity of having a long pull from the

bottle.

Women, though I used

to follow them for years with a chicken-bone in one hand and a piece of bread

in the other, were to me nothing more than distant Madonnas. Only

later on in life I began to realize that the motive of this much ridiculed behaviour can only be that

woman to an artist is the means to an end, while to others she is an end in

herself.

Song, however, cost me

more than money could pay. Musical pleasure such as opera displayed on the

stage was regarded as profane according to the religious conception of my

father, who in spite of his misinterpreted religious dogmas, used to improvise

symphonic music as an unconscious protest. To satisfy my spiritual extravagencies,

I was prepared to bear corporal and other punishments, which were in store for

me on coming home. But for the pleasure of opera, I even paid with my carving

tools which I usually gave in lieu of the entrance fee. Exchanging one art for

another seemed to me a better barter system than exchanging the poor sound of a

golden sovereign for the ethereal sound of Wagner's overture to Lohengrin.

My first serious

attempt at modelling started with an indescribable urge. I felt as if I were

loaded with rocks to be blasted by the fuse of the inner detonation of the

spirit. Because of my parents' disapproval, it was no easy task to find a

suitable manoeuvring field in which to let it go.

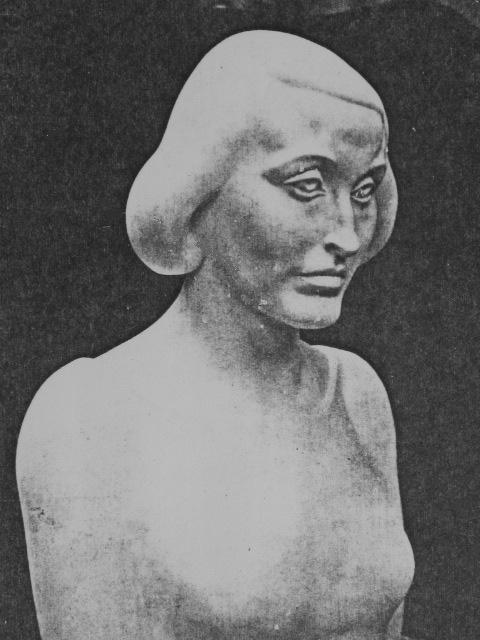

I had to start a bust

three times life-size in the pantry, which measured 2 ft. by 4 ft. There was no

space to step backwards - not even the three steps of respect which are paid to

art, or for general surveying. To the amazement of my friends I finished it. I

forgave the potential art lovers and critics for their flirtation with the

artist rather than the art. Hoping to cash in on their fast-cooling enthusiasm for

some sort of a bursary, I did not let them get away with their habit of using

pictures and artists as a signboard for their good taste and culture, painted

with someone else's blood.

The only inspiring

reaction I experienced was when I carried the bust out from the pantry into the

kitchen - the first stepping-stone towards a prima donna's fame - in order to

show it to my Father. While inspecting it I noticed a veil gradually lifting

from his eyes - a screen that separated the religious prejudice from the

instinctive understanding of the fine arts. He only shook his head in a noncommittal

way, not knowing whether to be for or against my career. Thus the pantry,

kitchen and studio became not only my favourite domestic environment, but also

my holy of holies.

My urge, like the

roaring elements, was not satisfied with this expansion from the pantry to the

kitchen, and I decided to face everything - family agitation, insecure material

prospect, and even the threat of the hard road to fame. I preferred the eternal

dilemma between a questionable comfort of life and resignation to simple and

more substantial pleasures, rather than to live with those whose idea of a

colourful life is to live like a beach-comber, not knowing that a creative

vagabond and a money-glorified and useless if not destructive, vagabond are not

the same.

So my vagabond career

started by going to Budapest, the most beautiful city in the world, the

gatepost between the East and the West where the mystical civilization of the

sunrise in the East meets the objective culture of the sun setting West. Since music is the thermometer of a

nation's temperament, the Hungarian composers can write a song with the breath-taking

finesse of a Frenchman and die for music with the self-denial of the East.

My first contact with

the Budapest Art Academy was full of anxiety, not because of the strictness of

it's Selecting Committee, but mainly because I could not attend all the eight

days of the Talent examination, on account of my singing which paid my way.

Though the judgement of the four professors for the academy was in my favour, I

was bewildered at the numerous requirements for becoming an artist. Nevertheless

I took them in with a feverish thirst for knowledge that still remains

unquenched today.

Vienna, the first

milestone in the Western civilization, and the lid on the boiling pot of the

Balkans, impressed me with her happy-go-lucky way of living in spite of having

to face the constant danger of being swamped by her over-boiling pot. She

waltzed her worries away through a carefree life, which can only be afforded by

people to whom having a good time means making a living, unlike those to whom

the pleasure of life means making a living.

Professor Hanak, my

teacher, and many other fine artists, were supplied with studios built in a

corner of the Vienna Woods, by an encouraging government. Walking every day to work accompanied

by a whistling symphony of the birds, the inspiring studio of many a great

composer, urged me to meditate, and greatly helped me in the process of

crystallization.

Stimulated by this atmosphere,

the shapeless rocks of art smouldering in my heart and mind began to grind

against each other they reached the refinement of the weightless dust called

art.

Berlin, the hot-point

in the manufacture of political, scientific, cultural and artistic events, appeared

to me like a patient on the day of a medical examination. While finding her

national temperature far beyond normal, it was impossible to diagnose whether

the flushed complexion was the fever of sickness or the glow of health.

Berliners look at

life through precision field-glasses enabling them to see the panorama from its

protoplasmic beginning to the decadence of the Homo Sapiens (in contrast to the

Viennese outlook on life and art). Berlin with her rustic left-handed

helplessness and heavy-booted clumsiness was trying to tip-toe her way up to

the Pantheon of the Frenchman, the only nation that managed to do away with the

clumsiness of matter, and to convert it into the spirit of a Rodin, Degas,

Renoir, Debussy, Hugo, Balzac, etc.

Paris, the

nerve-centre of the art world, made my heart beat in a tempo that echoes the

heart-beat of every artist all over the world. Paris, the only broadcast house where the Muses sing love

songs of art to which every decent singing person form every corner of the

world listens in, which jams all interference of political, financial and

power-grabbing intrigues. Paris, the living university of life and art., the

only authority to bestow degrees,

gave me the understanding

of the meaning of art, namely the transfiguration of a figure from Nature’s

self-preservation scheme to the higher purpose art, the reflection of the spirit

of each epoch as seen through the eyes of the artist. Paris, with its open-air

theatre of world-breaking dramas and diaphragm-bursting comedies, not acted,

but lived by every Frenchman as Shakespeare meant it for the stage, taught me

that art must be lived.

London, the Queen of

the Imperial beehive, possesses a natural temperature that cannot be measured

with the same thermometer as that applied to other European nations. As in the life

of bees, her emotional life is subjected to the Queen in order to maintain the

complicated channel system of her Empire. She, therefore, cannot afford to

exhibit her sentimental life. This may give the impression that love-making is

to the British simply doing a job like any other job. Yet, beneath her channels

the waters run deep unlike other nations that have no channels to serve as an outlet,

and which, therefore, over-sentimentalise each other, while Britain keeps cool.

In the year 1931-32,

London's awakening to modern art consciousness appeared like a whirlwind and

swept away her conservative tradition with a vigour that cleansed the art

studios and turned them into a worthy place fit for any representative of

modern sculpture, such as Epstein the symbolist, Henry Moore the formalist, and

Frank Dobson the dynamical. Indeed, these representatives embody the whole

scale of the emotional complex of humanity. They prove that personal and

national temperament are not measured by the wobbling of our anatomy to the

tune of the boogey-woogey, but by the inward forces, the vibration of which, tears

our anatomy without moving a muscle. In other words, here I realized that to

express the most dramatic ecstasy with the least movement is the unwritten law

of modern art.

South Africa, God's

virgin country, and unspoiled by civilization, has a very talented urge for

culture. The culture that was the twilight of European decay, is now becoming

the daylight of South Africa’s awakening. Not being afraid of the dangers of a crumbling civilization

in the world, is the sign of her daring

youth. By emerging from

Bushman's art and by leaving behind the heritage of Europe, she enters now the

broadness of her sunlit landscapes and of other cultural expressions.

With the outbreak of

the Second World War, my vagabond life was interrupted. The shocking news of

the cold-blooded murder of my co-vagabond poet, induced me to sign the dotted

line, and I became an active member of the South African army. This meant no

more curved lines for the duration. Having had no chance to carve stones, I

overcame the boredom of the evenings in Camp with thoughts about life, which resulted

in the creation of "Carved Thoughts".